HON’s Wiki # IPv6 Theory

Home / Networking

Contents

Resources

- IETF RFC 7381: Enterprise IPv6 Deployment Guidelines

- IETF RFC 7755: SIIT-DC: Stateless IP/ICMP Translation for IPv6 Data Center Environments

- IETF RFC 7934 (BCP 204): Host Address Availability Recommendations

- IETF RFC 8200 (STD 86): Internet Protocol, Version 6 (IPv6) Specification

- APNIC: IPv6 Best Current Practices

- apenwarr: The world in which IPv6 was a good design

Special Prefixes and Addresses

| Prefix | Scope | Description |

|---|---|---|

::/0 |

Default route | |

::/128 |

Unspecified | |

::1/128 |

Host | Localhost |

::/96 |

IPv4-compatible IPv6 address (deprecated) | |

::ffff:0:0/96 |

IPv4-mapped IPv6 address | |

::ffff:0:0:0/96 |

IPv4-translated IPv6 address | |

64:ff9b::/96 |

IPv4-embedded (e.g. NAT64) | |

100::/64 |

Discard-only (RTBH) (RFC 6666) | |

2000::/3 |

Global | Global unicast address (GUA) |

2001::/32 |

Teredo | |

2001:20::/28 |

ORCHIDv2 | |

2001:db8::/32 |

Documentation (non-routable) | |

2002::/16 |

6to4 (deprecated) | |

3ffe::/16 |

IPv6 Testing Address Allocation (6bone) (reverted) | |

fc00::/7 |

Site | Unique local address (ULA) |

fd00::/8 |

Site | Locally administered ULA |

fe80::/10 |

Link-local | Link-local unicast (non-routable) |

ff00::/8 |

Variable | Multicast |

See the IANA IPv6 Special-Purpose Address Registry for an updated table.

Multicast

| Prefix | Scope | Description |

|---|---|---|

ffx2::/16 |

Link | Link-local scope |

ffx5::/16 |

Site | Site-local scope |

ffxe::/16 |

Global | Global scope |

ff02::1 |

Link | All-nodes |

ff02::2 |

Link | All-routers |

ff02::6a |

Link | All-snoopers (multicast router discovery) |

ff02::fb |

Link | mDNSv6 (link-local) |

ff05::fb |

Site | mDNSv6 (site-local) |

ff02::1:2 |

Link | All-DHCP-relay-agents-and-servers |

ff05::1:3 |

Site | All-DHCP-servers |

ff02::6b |

Link | PTPv2 messages |

ff02:0:0:0:0:1:ff00::/104 |

Link | Solicited-node |

ff0x::/96 |

Any | Source-specific multicast (SSM) |

Subnet Addresses

- Subnet-router anycast address: The first interface ID in every subnet (RFC 4291). (Does not apply to /127 and /128 addresses.)

- Subnet anycast addresses: The last 128 interface IDs in every subnet (RFC 2526). (Does not apply to /127 and /128 addresses.)

Advantages over IPv4

- Designed based on experience with the strengths and limitations of IPv4 and other protocols.

- IPv4 is becoming obsolete.

- An investment in IPv4-only is an investment in EOL technology.

- Certain services may only be available over IPv6 in the future.

- IPv4 will be provided as a service in the future, making it less performant than native IPv6.

- Since you’ll need it some day, it’s better to get familiar with it early.

- While still needed for the full internet, internal networks may be IPv6-only.

- Larger address space.

- Much simpler and more structured address plans. Hexadecimal representasion and subnetting on nibble boundaries means no more IP calculators are needed for simple calculations.

- All subnets are (should be) /64 regardless of the number of hosts/interfaces (even linknets!). No more planning for the number of hosts in a subnet.

- Extra information can be embedded in the address.

- No need for NAT.

- Restores end-to-end princible.

- Better peer-to-peer support.

- Improved protocols like ICMPv6, NDP, MLD and DHCPv6.

- Native support for IPsec.

- Stateless address autoconfiguration (SLAAC) reduces administrative overhead for simple networks.

- Improved QoS.

- Improved multicast.

- Removed broadcast (use-cases instead use multicast).

- Interfaces can (and typically do) have multiple addresses.

- One link-local address.

- One or more addresses for each different advertised prefix from each local router.

- More efficient routing due to better address aggregation (generally).

- More efficient packet processing:

- Streamlined fixed-length header with extension headers.

- No fragmentation in routers.

- No checksum.

- Although, variable number of extension headers, can make the packet header stack harder to check.

Addressing

- 128 bit addresses.

- No broadcast (uses multicast for those use-cases instead).

- All subnets are /64, even point-to-point linknets.

- Anycast:

- Explicitly supported.

- May use any unicast address.

- Treated like unicast except by the last routers toward the hosts using the anycast address.

- Some important addresses:

- Subnet-router anycast: The first interface ID in every subnet. All routers are required to listen to it. (RFC 4291)

- Reserved: The last 128 interface IDs in every subnet. (RFC 2526)

- Shared unicast address approach:

- An alternative approach to anycast.

- Same as for IPv4, based purely on unicast and routing and no explicit anycast mechanisms.

- Multiple hosts using is as their unicast address and letting routing protocols route towards the closest one.

- Multicast:

- Some scopes:

- 1: Interface-local.

- 2: Link-local.

- 5: Site-local.

- E: Global.

- Some important addresses:

ff02::1: All-nodes (link-local).ff02::2: All-routers (link-local).ff02::3: All-hosts (link-local).ff02:6a: All-snoopers (link-local).ff02::1:ff00/24: Solicited-node (link-local).

- Some scopes:

- Solicited-node multicast address.

- Solicited-node prefix plus last 64 bits of an IPv6 address.

- Interface addresses:

- Addresses are assigned to interfaces, not hosts.

- Interfaces may have multiple addresses.

- All interfaces have a link-scoped address.

- Permanent and temporary address types.

- Address assignment:

- Static.

- Stateless address autoconfiguration (SLAAC).

- Stateless DHCP.

- Stateful DHCP.

- DHCP:

- See the section below.

- Similar to DHCPv6, but with some important changes.

- Generally used when indicated by router advertisements that DHCP should be used (stateful or stateless).

- Stateless DHCP instructs devices to use address autoconfiguration, but get additional data (e.g. DNS servers) from the DHCP server.

- SLAAC interface ID generation methods:

- Modified EUI-64 addresses:

- The first method of autoconfiguring an address, giving a single interface ID deterministically based on the MAC address (using the modified EUI-64 method).

- Useful for servers with autoconfigured addresses due to its stability, unlike temporary addresses that change over time.

- Privacy/temporary addresses (RFCs 3041, 4941, 8981):

- A set of extensions adding temporary, randomized addresses in order to preserve privacy by not revealing the MAC address (visble from the EUI-64) and also to periodically change the address.

- When a new address is generated, the existing ones are marked as deprecated and not used for new connections, but are kept to keep existing connections alive.

- While earlier RFCs called this “privacy extensions”, newer RFCs refer to this as “temporary address extensions”.

- Stable and Opaque addresses (RFCs 7217 and 8064):

- Uses a single, deterministic address based on the host and the subnet.

- This avoids having to change the address as in temporary address extensions and avoids MAC-trackable addresses as in modified EUI-64 addressing.

- This is now the default in RFC-compliant IPv6 stacks.

- … and other methods like Cryptographically Generated Address (CGA) and Hasb-Hased address (HBA).

- Modified EUI-64 addresses:

- Reserved subnet addresses:

- The first and last addresses in a subnet are not reserved and it’s possible be assigned to hosts, unlike IPv4 (i.e. the network and broadcast addresses).

- However, address zero is reserved for the subnet-router anycast address and the last 128 addresses are reserved for other subnet anycast addresses.

- Address states:

- Tenative: Waits for DAD to finish.

- Preferred: Can be used.

- Deprecated: About to expire. Can be used for existing connections but not new ones.

- Valid: Preferred or deprecated.

- Invalid: Expired valid.

- Optimistic: Like tenative but for Optimistic DAD. Can be used.

- Point-to-point linknets:

- Use /64, not /127. “Everything is a /64” makes the address plan simpler, routing tables simpler and potentially improves TCAM utilization. Even if forced to use /127 on the link, reserve the whole /64 for the link.

- /127 was formerly recommended when certain vulnerabilities with /64 linknets was discovered (i.e. neighbor cache exhaustion, see RFC 6164). However, those vulnerabilities are now fixed (mainly ICMP error rate limits and memory limits) and /127 is no longer needed.

- In many early implementations, everything had to be a /64, including linknets and loopbacks, so using /127 and similar might break certain implementations.

- While the linknet may use ULA or even link-local (unnumbered), use GUA whenever you can. It makes the address plan and routing tables cleaner and allows traceroute and similar to work.

- Common address selections inside the linknet includes

aandb.0and1is also often used, but0will generally be compressed away so that one of the addresses look weird.

Packet Structure

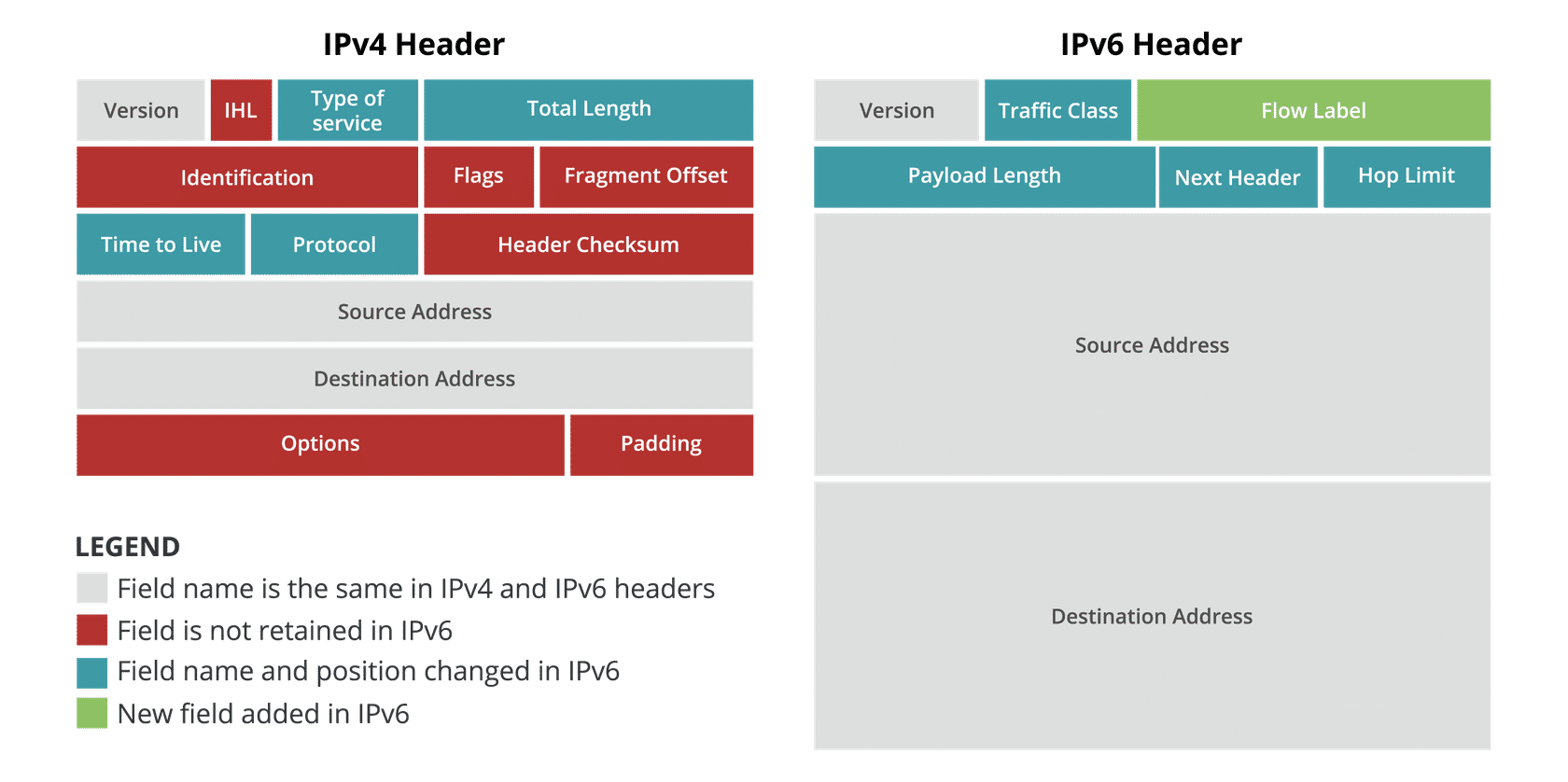

Figure: Packet header differences between IPv4 and IPv6. (Source: RIPE)

- Overall, IPv6 replaced the variable-length IPv4 header with options and stuff (20 bytes or more) with a streamlined, constant-length bases header (40 bytes) and an optional chain of extension headers.

- List of “next header” protocols: IANA: Protocol Numbers

Changes from IPv4

- Changed the value of the “version” field from 4 to 6.

- Removed the “internet header length” (IHL) field, the base header is constant-length now.

- Removed the “identification”, “flags” and “fragment offset” fields, fragmentation is handled by the fragmentation header now.

- Removed the “header checksum” field, since checksumming is often done by both lower-level and higher-level protocols.

- Removed the “options” field and its padding, options are now replaced by EHs.

- Replaced the “type of service” (ToS) with the “traffic class”, used for the same purpose. Actually split into a DiffServ field and an ECN field for both protocols.

- Replaced the “total length” field (size of header and payload) with the “payload length” field (size of payload, including EHs).

- Replaced the “time to live” (TTL) field with the “hop limit” field. Whereas the IPv4 TTL was meant to represent time in seconds, the IPv6 hop limit now specifies the number of hops instead, which is generally how TTL was implemented anyways.

- Replaced the “protocol” field with “next header” field, giving the type of the next EH or the upper-layer protocol if no EHs (like the last EH).

- Added the “flow label” field, allowing the use of explicit flows instead of the implicit 5-tuple flow definition. A zero value means no flow classification. The flow label indicates to intermediate hops that the packets in the flow should travel along the same path, preventing reordering and stuff.

Extension Headers (EHs)

- IPv6 in theory allows an arbitrary amount of EHs chained together (the “header chain”), but normally there are none for simple traffic.

- There currently exists a limited number of standardized EHs, some listed below. They can only appear once in the header chain (excluding the destination options header, which might appear twice) and must appear in the correct order. New EHs can be created and standardized, but not without a good reason why an existing one can’t be used. For simple options, the destination options header can probably carry them instead of creating a new EH type.

- Some EHs may contain multiple options inside, for instance the destination options header, which may be used for carrying new/non-standard options.

- Most EHs are only processed by endpoints, except the hop-by-hop and routing headers.

- Each EH, as well as the base header, specifies the protocol number of the next header. The very last header (base or extension) specifies the protocol of the upper-layer PDU.

- While the base header was made more “streamlined” by making it constant-length, it can maybe be argued that the chain of EHs makes the whole IPv6 packet less streamlined as each header must be examined to find the start of the upper-layer PDU, where e.g. the TCP/UDP port numbers may be found (e.g. for filtering or NAT/PAT purposes).

- Current EHs as of RFC8200 (in recommended order):

- Hop-by-hop options: For intermediate nodes, containing suboptions in the TLV format. Should be immediately after the base header.

- Routing: For source routing.

- Fragment: For fragmentation, which must be done by the sender.

- Authentication header (AH): For IPsec.

- Encapsulating security payload (ESP): For IPsec. May be followed by either a destination options header or the upper-layer PDU.

- Destination options: Similar to hop-by-hop options, but for the destination. May be used twice if used together with a routing header, in which the first one should be immediately before the routing header.

- Fragmentation header:

- Routers no longer fragment, it’s now the sole responsibility of the source endpoint. Only the destination endpoint is allowed to reassemble fragments. This avoids wasting processing power of intermediate routers and might prevent certain fragmentation attacks.

- All fragmentation options are now contained within the fragment EH. Its main fields are the fragment offset (13 bits, in 8-octets), an M flag (“more fragments follows”) and an identification number (32 bits).

- Fragment reassembly should use a reassembly timer and must be able to handle fragmentation attacks (e.g. small or overlapping fragments).

- Path MTU discovery is used to discover the path MTU, i.e. the minimum link MTU in the path.

- RFC 6980 forbids fragmented NDP packets, as it can be used in attacks against e.g. RA guard. This forces hosts to discard fragmented NDP packets.

- The first fragment must contain all EHs.

- Routing header:

- It describes one or more IP addresses that should be visited on the path toward the final destination, containing options that are processed by the visited nodes.

- The header fields describe the header length, the routing type, the number of segments left on the path and data specific to the routing type (i.e. options).

- See IANA for the supported and deprecated routing types.

- Routing header type 0 (RH0) was previously found to be dangerous to the Internet and has been deprecated (see RFC 5095). It could be used to flood a remote path/link using 127 addresses, such that the packet bounces between the two path endpoints around 126 times, giving roughly a 63x traffic amplification in both directions on the path. To mitigate, avoid using RH0.

- RFC 7872 describes real-world observations of packet drops caused by EHs.

- Draft “draft-ietf-opsec-ipv6-eh-filtering-10” presents recommendations for filtering IPv6 traffic with EHs.

Protocols

Internet Control Message Protocol for IPv6 (ICMPv6)

- Used for error messages (e.g. “packet too big”) and informational messages (e.g. echo, NDP and MLD).

- Just like ICMPv4, the header contains an 8-bit type, and 8-bit code and a 16-bit checksum (32 bits total).

- The code functions as a sub-type to provide a more detailed error.

- Format:

- ICMPv6 packets follow either the general format or the extended format.

- The general format is used by “packet too big” and “parameter problem”. “packet too big” contains the MTU and “parameter problem” contains a pointer to which byte of the IPv6 packet that contains a problem, followed by as much of the original packet as possible, without the ICMP packet exceeding 1280 bytes.

- The extended format adds a length field at the start of the body and and extension structure at the end of the body (after parts of the original packet). The extension structure contains a header and one or more objects, each containing an object header and an object payload.

- The extended format is used by “destination unreachable” and “time exceeded”.

- Error messages (4 main):

- Type 1: Destination unreachable (8 codes).

- Type 2: Packet too big.

- Type 3: Time exceeded (2 codes).

- Type 4: Parameter problem (3 codes).

- Informational messages (includes MLD and NDP):

- Type 128: Echo request.

- Type 129: Echo reply.

- Type 130 (MLD): Multicast listener query.

- Type 131 (MLD): Multicast listener report.

- Type 132 (MLD): Multicast listener done.

- Type 133 (NDP): Router solicitation (RS).

- Type 134 (NDP): Router advertisement (RA).

- Type 135 (NDP): Neighbor solicitation (NS).

- Type 136 (NDP): Neighbor advertisement (NA).

- Type 137 (NDP): Redirect message.

- Type 143 (MLD): Multicast listener report v2.

- … and more.

- Se IANA for an updated list of ICMPv6 parameters.

- Error messages not known by the known should be forwarded to upper-layer protocols to interpret them, according to standard. One should consider filtering not needed ICMP messages.

- While ICMPv4 may be blocked without completely breaking IPv4, IPv6 will break if ICMPv6 is blocked, due to NDP being a part of ICMPv6 and ARP not being a part of ICMPv4.

- ICMPv6 error messages must not be sent in response to packets destined to a multicast address, as this can be used for discovery and amplification attacks (RFC 4443). This does not apply to “packet too big” and “parameter problem”, however.

- Responding with a “echo response” to an “echo request” sent to a multicast address (aka a multicast ping) is optional. Most OSes nowadays don’t do this by default.

- Received ICMPv6 informational messages with an unknown type must be silently discarded. This prevents discovery.

- Nodes must rate limit their originated ICMPv6 error messages.

Neighbor Discovery Protocol (ND or NDP)

- Uses ICMPv6, types 133–137.

- Provides:

- Router advertisements.

- Link-layer address resolution (similar to IPv4 ARP).

- Neighbor unreachability detection (NUD).

- Duplicate IP address detection (DAD).

- Redirect messages.

- Neighbor cache:

- Contains entries about recently discovered neighbors, keyed on the neighbor’s on-link address.

- Entry contents:

- The Link-local address.

- A flag indicating if it is a router.

- A pointer to any queued packets waiting for address resolution to complete.

- Reachability state (NUD).

- Etc.

- Entry states:

- INCOMPLETE: Initial address resolution is taking place.

- REACHABLE: Reachability recently confirmed. This typically lasts for 30 seconds after the last traffic.

- STALE: Reachability expired, but it will still be used and will transition to DELAY when a packet is sent.

- DELAY: A packet was recently sent from STALE, we’re waiting for a response packet. If none is received in time, start NUD and transition to PROBE.

- PROBE: NUD is taking place, typically sending 3 NSes with 1-second spacing. (If it fails, some implementations may transition to an implementation-defined FAILED state.)

- Destination cache:

- Contains entries about recently used on-link and off-link destinations.

- Maps a destination IP address to the IP address of the next-hop neighbor, which may then bee looked up in the neighbor cache.

- Redirect messages update this cache.

- Entries may also contain information such as the path MTU and round-trip timers maintained by transport protocols.

- Duplicate IP address detection (DAD).

- Determines if the address is unique before it can be used.

- Opportunistic DAD allows using the address before DAD finishes (used by Windows).

- Router advertisements.

- SLAAC or DHCPv6.

- M-bit (managed address configuration flag): If DHCPv6 is used to assign host addresses.

- O-bit (other configuration flag): If DHCPv6 can be used to obtain more information (e.g. DNS servers). Ignored if M-bit is set.

- L-bit (on-link flag) (for prefix): If the prefixes are directly reachable on the link, so the host can reach them without going through the router.

- A-bit (address configuration flag) (for prefix): If the host can generate a SLAAC address using this prefix. Can be set together with M-bit for fun results.

- RA messages are required to originate on-link, have a link-local source address, and have a hop limit value of 255 (RFC 4861).

- See RFC 7113 for RA guard security details.

- Uses a hop limit of 255 and requires hosts to discard arriving packets with lower hop limits. This prevents NDP attacks from outside the local network.

- RFC 6980 forbids fragmented NDP packets, as it can be used in attacks against e.g. RA guard. This forces hosts to discard fragmented NDP packets.

- IPsec may be used for ND messages, but in practice it is not used.

- Identification of ND messages:

- All-zero to solicited-node: Duplicate address detection (DAD).

- Unicast to solicited-node: Link-layer address resolution.

- Unicast to unicast: Neighbor unreachability detection (NUD).

- Secure neighbor discovery (SEND):

- Router authentication.

- Cryptographically generated address (CGA).

- Some security options.

- Standardized (RFC 3971) but not widely available, so it can’t be reliably used.

- Other RFCs:

- RFC 3122 proposes Inverse neighbor discovery (IND).

- RFC 7048 proposes changes to NUD and an extra UNREACHABLE neighbor cache state.

- RFC 7527 proposes an enhanced DAD, which is able to detect looped-back DAD messages and self-heal after the problem is fixed.

- RFC 9131 proposes Gratuitous Neighbor Discovery.

Multicast Listener Discovery (MLD)

- Uses ICMPv6, types 130–132.

- For registration of multicast listeners within a subnet, similar to IGMP in IPv4.

- Since multicast is mandatory for NDP to function, MLD is required for IPv6. NDP requires the host to join multiple multicast groups, e.g. the all-nodes group and the solicited-node group.

- MLDv1:

- Based on IGMPv2, using any-source multicast (ASM).

- Support is no longer mandatory.

- Messages:

- Query (ICMP type 130): Sent by routers to query the subnet for listeners for all groups (general, sent to all-nodes group) or a specific group (specific, sent to specific group).

- Report (ICMP type 131): Sent by hosts to join a group or to respond to queries, sent to the respective group.

- Done (ICMP type 133): Sent by hosts to leave a group, sent to the all-routers group.

- MLDv2:

- Based on IGMPv3, using source-specific multicast (SSM).

- Support is mandatory.

- Compatible with MLDv1. If a link has any MLDv1 nodes, all nodes must operate in MLDv1-compatible mode.

- Messages:

- Query (ICMP type 130): Same as MLDv1, but adds the group-and-source-specific query type to query if a list of sources for the group has any listeners, sent to the group address.

- Report v2 (ICMP type 143): Similar to MLDv1 Report, but also takes the role of MLDv1 Done for hosts leaving a group. It’s sent to the all-MLDv2-capable-routers group (

ff02::16). It’s a “state change report” if sent because of group membership changes, or a “current state report” if sent in response to a query.

- For a certain group, a node can use either include filter mode or exclude filter mode to filter which sources it wishes to receive traffic from. Lightweight MLDv2 (RFC5790) only allows include filter mode.

- All MLD messages shoud be sent with a hop limit of 1, to keep all traffic on the link. Additionally, only link-local addresses should be used as source addresses.

- All MLD messages should include the hop-by-hop header with the router alert option set, so that routers can naturally receive MLD messages for groups they’re not a member of.

- MLD snooping can be used by switches to optimize switching. It only allows multicast traffic on ports with listeners. It does not protect against any threats.

- To prevent downlink switch ports from sending queries, enable MLD protection on the switches through an ACL that blocks ICMPv6 MLD query messages.

- To protect routers from resource exhaustion, enable memory limits and rate limits.

- PIM can be used for routed multicast (between subnets).

- Multicast router discovery (MRD):

- Based on MLD.

- For discovery of multicast routers.

- Configuration and commands: See Multicast.

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol for IPv6 (DHCPv6)

- Optional for IPv6 address assignments, SLAAC may be used instead.

- Relies on RAs to provide the default route and start trigger DHCP discovery.

- Stateful (with address assignment) or stateless (without address assignment).

- Uses UDP port 546 for clients and 547 for servers (DHCPv4 uses ports 68 and 67).

- Instead of broadcasting as in DHCPv4, DHCPv6 clients use the multicast address

ff02::1:2(all DHCP relay agents and servers). DHCP relays may useff05::1:3(all DHCP servers) to reach upstream servers, but typically have the DHCP server unicast addresses configured instead. - Reconfiguration messages are sent by the server to indicate changes (not possible in DHCPv4).

- Supports relays, same as DHCPv4.

- Uses DHCP Unique Identifier (DUID) to identify clients (DHCPv4 uses plain MAC addresses).

- Client messages:

- Solicit: Like DHCPv4 discovery, a client wants address offers.

- Request: Like DHCPv4 request, a client requests an IP address from a new offer.

- Confirm: The client did a successful DAD on a newly assigned address.

- Decline: Unlike Confirm, the DAD failed and the address can’t be used.

- Renew: A client wants to renew its lease.

- Rebind: Sent after a Renew went unanswered.

- Release: A client releases its leases.

- Information-Request: For stateless DHCP, a client wants to know stuff. The server responds with a Reply.

- Server messages:

- Advertise: Like DHCPv4 offer, a server offers an address.

- Reply: Like DHCPv4 acknowledge, the server responds to a request.

- Reconfigure: The server indicates that information has changed, and the client must fetch it using Renew/Reply or Information-Request.

- Relay messages (to/from servers):

- Relay-Forw: Messages relayed from client to server.

- Relay-Reply: Messages relayed from server to client.

- Address allocation strategies:

- Iterative: Simple, non-deterministic. Vulnerable to enumeration attacks.

- Identifier-based: Gives an address based on some fixed identifier, such that it typically gets the same address each time. May leak the identifier.

- Hash allocation: Like identifier-based allocation, but hashes the identifier to avoid leaking it directly.

- Random allocation: Non-deterministic and the most privacy-preserving option.

- Identity Association (IA):

- One per interface.

- Contains IPv6 addresses plus timers.

- Clients must perform DAD after being allocated an address by the server.

- Rapid commit option (only two messages) may be used if supported by both the client and the server.

- DHCP Prefix Delegation (DHCP-PD):

- Allows clients to request prefixes to be routed to them.

- Typically used between home network CPEs and ISPs to get dynamically assigned an /56 IPv6 prefix to address its internal networks from.

- The prefix exclusion option may be used by the delegating router to reserve subprefixes for e.g. the downlink (RFC 6603).

- Secure DHCPv6 (draft-ietf-dhc-sedhcpv6-21):

- Uses PKI to autenticate and encrypt client-server communication.

- DHCPv6-Shield (RFC 7610):

- Aka DHCPv6 guard or DHCPv6 snooping, using designated ports as trusted uplinks toward servers.

- IPsec can be used, especially between relays and servers.

- Android and Chrome OS does not support DHCPv6, by design.

- To help with traceability without DHCPv6, Netflow or periodic NDP cache scans with SNMP can be used.

Domain Name System (DNS)

- A6 (old) and AAAA type records.

- Dual stack hosts need two entries.

ip6.arpa. Originallyip6.int.- Dual stack clients query for both a A and an AAAA record for each domain name to resolve.

- The transport used is independent of the record type being queried for.

- Native IPv6 is generally preferred over IPv4.

- DNS whitelisting: Only respond with AAAA records to ISPs with good IPv6 performance.

- Happy eyeballs:

- Clients will attempt to connect using both IPv4 and IPv6 and use the faster one.

- IPv6 is preferred.

- Different implementations exist.

- Name space fragmentation:

- Every name server from the root (for a certain domain name) must be accessable by the resolver.

- IPv4 should always be supported.

Path MTU Discovery (PMTUD)

- Since IPv6 does not fragment along the path, knowing the path MTU is important.

- ICMPv6 error type 2 (“packet too big”) are send by routers along the path if the packet is too big, so the host can retry using a smaller packet.

- The minimum MTU for IPv6 is 1280 octets. 1500 octets is generally the default.

tracepathon Linux can be used to troubleshoot path MTUs.

IPSec

- IPsec provides authenticated and/or encrypted transport between two nodes.

- Baked into IPv6 using the AH and ESP extension headers.

- How it works (IPv4 and IPv6):

- The Security Policy Database (SPD) in the sending host decides wheather to protect (IPsec), bypass (no IPsec) or discard the packet, based on IP addresses and next laye header information.

- Security information for IPsec tunnels between two hosts, such as chosen cryptographic protocols and keys, is stored in Security Associations (SAs), one on each side for each direction of each tunnel. Both authentication (AH) and encryption (ESP) depoend upon the existance of SAs.

- SAs are typically created using Internet Key Exchange (IKE).

- IPsec is used wither in tunnel mode or transport mode.

- Tunnel mode:

- When a full IPv6 datagram (headers plus payload) is placed inside an encapsulating IPv6 plus IPsec datagram.

- Typically used between two routers providing an encrypted link between them, where existing, unencrypted traffic enters the first router and exits the second router.

- The full original packet is encrypted, effectively hiding the source and destination addresses and other header info.

- Transport mode:

- When the payload is placed directly after the IPv6 plus IPsec headers (only one layer of IPv6 headers).

- Used for end-to-end/host-to-host encryption, where IPsec is added when building the datagram.

- This mode places the processing overhead from the intermediate nodes in the network to the end hosts, giving a more distributed and potentially a more scalable structure.

- IPv6 IPsec headers:

- Extension headers that must be inspected by intermediate nodes (hop-by-hop, routing, fragmentation) must be placed unencrypted before the AH/ESP header.

- Authenticated Header (AH):

- Provides authentication and integrity services.

- Support in IPsec implementations is not mandatory.

- It generates a cryptographic hash using keys from the SAs, called an integrity check value (ICV). It hashes the base header (immutable fields only), the extension headers before the AH header (immutable fields only), the AH header itself (excluding the ICV), the following extension headers and the upper layer protocol. If used in tunnel mode, the hash includes the full encapsulated IPv6 headers.

- Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP):

- Provides authentication, integrity and confidentiality services.

- If not using encryption then it provides the same provides the same benefits as AH, although AH is more easily inspected by security devices.

- Support is mandatory in IPsec implementations.

- The extension headers after the ESP header are encrypted toghether with the upper layer payload. An ESP trailer is added to the end of the datagram.

- When using integrity checking as well, the ICV value is placed at the end of the datagram, after the ESP trailer.

Routing Protocols (Brief)

- Some use one shared instance for IPv4 and IPv6 while some use a separate instance for IPv4 (ships in the night), potentially different protocol versions.

- Best practices recommend using authentication between routing peers.

- RIPng:

- Limited diameter.

- Long routing loop convergence (count to infinity).

- Too simple metric.

- IPsec is recommended for authentication, but isn’t typically available in practice.

- OSPFv3:

- Originally it supported only IPv6 so IPv4 had to use OSPFv2, but now it supports IPv4 too through address families. In practice, IPv4 typically still uses OSPFv2, though, with some vendors lacking support for OSPFv3 address families.

- Differences from OSPFv2:

- Routes to links, not subnets.

- Uses link-local addresses for neighbors.

- Multiple instances per link.

- Removal of addressing semantics. IPv6 addresses are not present in OSPF headers.

- Flooding scope.

- Authentication.

- Implementations are required to either support IPsec ESP for authentication and confidentiality, or OSPFv3 authentication trailers containing a cryptographic hash using a shared key. As such, OSPFv3 is currently the only available IGP supporting encrypted route updates.

- IS-IS:

- Single instance for both IPv4 and IPv6.

- Supports HMAC-SHA authentication.

- EIGRP.

- MP-BGP:

- Multiprotocol NLRI gives implicit support for carrying other protocols such as IPv6.

- Supports TCP Authenticated Option (TCP-AO) for authentication, but the obsolete TCP MD5 signature option is still more widely used.

Transition Technologies

- Dual-stack:

- The best option for clients.

- Requires running two separate protocol stacks, which may be extra operationally expensive.

- Tunneling:

- Should use source address verification and ingress filtering.

- May bypass firewalls.

- Manual or automatic.

- Loopback encapsulation and routing-loop nested encapsulation. Partially avoided using the encapsulation limit option.

- Translation:

- Stateless or stateful.

- May use the well-known prefix

64:ff9b::/96. - May need to (re)calculate checksums both at multiple layers.

- Differing features (e.g. fragmentation and extension headers) may break.

- While NAT44 is required in IPv4 to counteract address depletion, NAT66 is not recommended for IPv6.

Tunneling Mechanisms

- 6to4:

- Deprecated.

- Only 6to4 routers/gateways need to be 6to4 aware.

- IPv6 Rapid Deployment (6rd):

- Widely used.

- Based on 6to4.

- Uses the ISPs own IPv6 range for customers.

- Stateless.

- Changing the customer IPv4 address also changes the IPv6 prefix.

- Intra-Site AUtomatic Tunnel Adressing Protocol (ISATAP):

- Must be supported by all nodes in the network.

- Teredo:

- May traverse NAT.

- Vulnerable if not configured properly.

- Should generally be avoided.

- May be enabled by default on some OSes. Disable it if not explicitly needed.

- Tunnel brokers:

- E.g. Hurricane Electrics and SixXS.

- Requires a public IPv4 address.

- MPLS.

- Locator ID Separation Protocol (LISP):

- General architecture not purely designed for IPv6 support.

- Separates IP addresses into two namespaces: Endpoint identifiers (EIDs) and routing locators (RLOCs).

- Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE):

- Manual.

- Can’t traverse NAT.

- Proto 41 forwarding:

- Allows nodes behind NAT to connect to tunnel servers on the internet.

- SSH.

Translation Mechanisms

- IP masquerading aka NAT44 (IPv4 only).

- Limitations (apply to many other NAT approaches as well):

- Port exhaustion: Some applications use a lot of connections, making port exhaustion a real threat when many users share the same port range.

- Violates end-to-end connectivity: A core Internet principle. The external hosts can’t address and connect to the internal host. For layer 4 and higher protocols, like UDP and TCP, port forwarding or hole punching must be used to connect to the internal host. Layer 3 protocols, like ICMP, won’t be able to traverse the NAT router. Protocols that embed the address in the payload, like IPsec, will generally not work without special handling.

- Prevents unique identities: Host can not be identified with unique IP addresses, which may cause multiple problems. Service providers will not be able to identify hosts doing participating in illegal activities, like attacking some server or downloading illegal content. IP blocking (as a result of offensive activities) and throttling will affect all hosts sharing the same public IP address, which may be accidental or intentional DoS. Service providers (like game platforms) may flag and block the IP address when many users are concurrently using the same services, because it thinks it’s a bot.

- Limitations (apply to many other NAT approaches as well):

- Carrier grade NAT (CGN) aka NAT444 (IPv4 only).

- Preserves even more IPv4 address space than NAT44.

- May be a good approach for providing native IPv4 as a service when most traffic is using IPv6.

- NAT464:

- IPv6-only between the customer edge and the privider network.

- Uses NAT46 and NAT64 at the two sides.

- DS-lite:

- IPv6-only between customer edge and CGN.

- IPv4 traffic is tunneled, not translated.

- Uses a DS-Lite basic bridging broadband element (B4) within or directly connected to the CPE.

- Uses a DS-Lite address family translation router (AFTR) within the provider network.

- The B4 creates a tunnel to the AFTR.

- The AFTR also functions as a NAT44.

- There is a DHCPv6 option for DS-Lite.

- Uses the range

192.0.0.0/29, where192.0.0.1is used by the AFTR and192.0.0.2is used by the B4.

- Stateless NAT64:

- Appropriate for IPv4-only servers so they can be reached by IPv6 clients.

- Uses prefix

64:ff9b::/96or a custom prefix. - 1:1 mapping between IPv4 and IPv6 addresses.

- Sessions can be initiated from both sides.

- Stateful NAT64 and DNS64:

- See section below.

- XLAT464:

- Uses stateful translation in the core and statekess translaton at the edge.

- Uses a customer-side translator (CLAT) which translated between 1:1 private IPv4 addresses and global IPv6 addresses.

- Uses a provider-side translator (PLAT) which translates between N:1 global IPv6 addresses and global IPv4 addresses.

- The NAT64 prefix can be aquired by querying the configured DNS server for

ipv4only.arpa. - It does not support inbound IPv4 connections or peer-to-peer.

- Implemented in Android.

- MAP.

- NPTv6 (IPv6 only):

- Statelessly translated between two equal-length IPv6 prefixes.

- Provides address independence: The internal network does not need to be renumbered when the public/external IPv6 prefix changes.

- May be used for multihoming.

- Does not need to rewrite port numbers in packets, but may break e.g. IPssec.

- May require split DNS since the external and internal addresses differ.

- NAT66 (IPv6 only):

- Like NAT44, including all its problems.

- Stateful.

Stateful NAT64

- Appropriate for IPv6-mostly client networks that still need access to the IPv4 Internet.

- Similar to typical NAT44, in the sense that multiple internal clients are dynamically mapped between a small pool of public IPv4 addresses.

- NAT64 prefix:

- Uses the well-known prefix

64:ff9b::/96or a custom prefix from your own address space (/96). - Custom prefixes can be distributed to clients using two methods:

- Using DNS (RFC 7050): The special domain name

ipv4only.arpa.may be queried to get the NTA64 prefix. - Using PREF64 (RFC 8781): The PREF64 RA option contains the prefix to be used for NAT64.

- Using DNS (RFC 7050): The special domain name

- Uses the well-known prefix

- DNS64:

- No changes are required in the IPv6 client in order to support it (i.e. no CLAT support is needed).

- If the DNS64 server does not find an AAAA record, it synthesizes a AAAA record within the NAT64 prefix.

- It can choose to not answer any A queries, if there are no IPv4 clients that need them (i.e. for IPv6-only networks and/or with clients with CLAT support).

- Should only be accessible from clients with IPv6 and reachability to the NAT64 translator.

- CLAT (client-side translator):

- An implementation on many client OS-es that received IPv4 traffic and translates the destination to the NAT64 prefix.

- Removed the need for DNS64, which suffers from DNSSEC breakage and doesn’t handle IPv4 literals in client programs.

- DHCPv4 option 108:

- To tell IPv6-capable clients to disable their IPv4 stack for a certain period of time.

- Clients that don’t support the option will simply continue with the DHCPv4 transaction to request an IPv4 address (if a pool is configured), such that IPv4-only devices will still work in the IPv6-mostly network.

- Limitations:

- See NAT44 limitations.

- All clients must be configured to use the the DNS64 server (e.g. through DHCP). Clients with statically configured public servers (UDP 53, DoT or DoH) will not work.

- All IPv4 addresses must have an associated domain name which must be used in place of the address literal. This may not always be the case, e.g. when people host stuff from home and use the IPv4 address directly.

- Some applications just don’t support IPv6, or may use IPv4 literals (hardcoded or acquired dynamically). They won’t work, period.

- Synthesized DNS records break DNSSEC. I’m not sure if typical clients validate DNSSEC, though.

- Required components:

- The NAT64 prefix (well-known or custom): Typically the well-known one for simplicity.

- The NAT64 translator: Typically a firewall, as it requires state. Must be configured with the well-known NAT64 prefix (which must be routed to it) and an outside IPv4 pool to translate to.

- A DNS64 server: Self-hosted with well-known or custom prefix or public with well-known (i.e. Google).

- CLAT support in clients: Supported in Android, iOS, macOS. Partially supported on Windows and Linux. Not supported by most older and IoT devices.

- PREF64 support in RAs: To tell the client to enable its CLAT with the included prefix.

- Option 108 support in the DHCPv4 server: To tell IPv6-capable clients to disable their IPv4 stack for a certain period of time. Clients that don’t support the option will simply continue with the DHCPv4 transaction to request an IPv4 address (if a pool is configured), such that IPv4-only devices will still work in the IPv6-mostly network.

Security

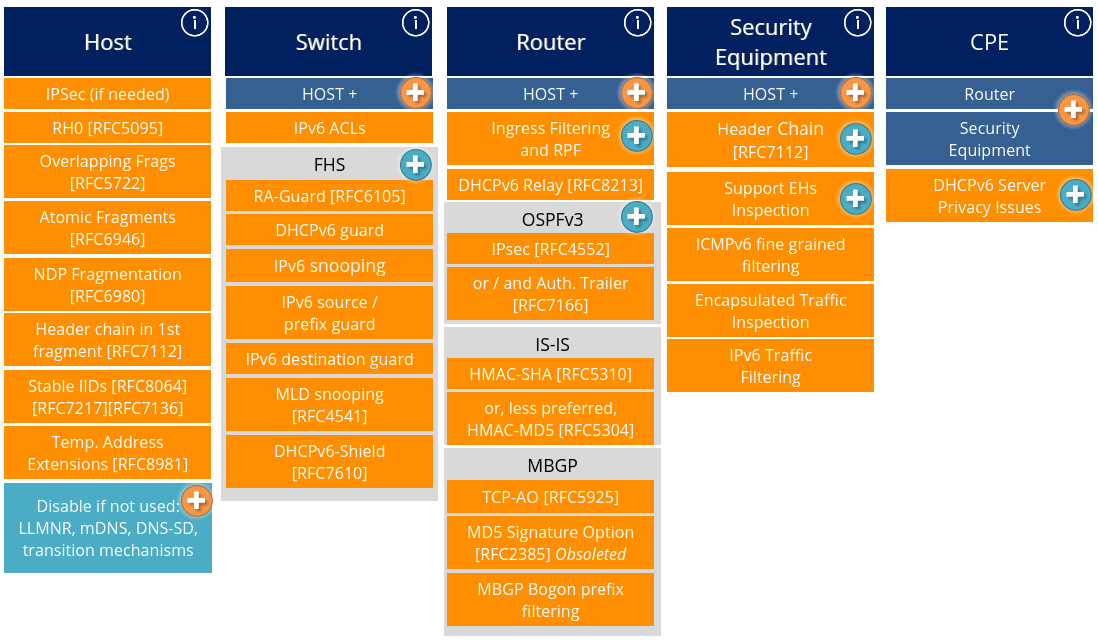

Figure: RIPE-722 “Requirements for IPv6 in ICT Equipment” overview. (Source: RIPE)

- Many actors are starting to realize that IPv6 is a thing and a potential attack surface.

- As most other things, security should be integrated into standards and implementations from the very beginning.

- Security policies should be IP version-agnostic, both at higher and preferably lower levels.

- IPv6 support in network devices:

- It’s not a yes/no question, as one could assume.

- There are a large amount of IPv6 features which some vendors implement and some don’t. Some simply say “yes”, some have documentation on what is implemented.

- See RIPE-772 (“Requirements for IPv6 in ICT Equipment”) or NIST/USGv6 (“NIST IPv6 Profile”) for templates/profiles used to certify levels of IPv6 support.

- Verify that the IPv6 features actually work as expected, especially security mechanism one could just assume work correctly.

- For end-to-end security, IPv6 has IPsec baked-in using extension headers, whereas IPv4 runs IPsec entirely in upper-layer protocols.

- Extension headers are an added challenge for security tools, due to its chained and variable-length structure and since all extension header types must be known and analyzed.

- Measures against network scanning:

- Use random interface IDs (especially for client networks).

- Use an IPS that can detect and block scanning attempts.

- Traffic filtering or rate limiting may be used.

- Avoid leaking internal routing information, e.g. by accidentally enabling OSPF on client networks.

- Deploy an IDS like Snort/Suricata/Zeek to find attacks and a vulnerability scanner like OpenVAS/Nessus to find vulnerabilities. NGFWs may come with these features as built-in proprietary solutions, but using a few open-source tools in addition may be a good idea.

- Stay up to date:

- Follow IETF for new RFCs, BCPs and stuff.

- Follow RIPE for BCPs and recommendations.

- Follow your network vendors for specific vulnerabilities and patches.

- Follow cybersecurity organizations for general vulnerabilities and recommendations.

- Follow vulnerability databases like CVE or NVE for current vulnerabilities affecting your products.

Traffic Filtering

- Generally applied by host firewalls, simple network firewalls (stateful L3-L4), NG network firewalls (stateful L3-L7 + IDS) or router/switch ACLs (stateless).

- Since IPv6 uses public addresses (GUA), unlike modern IPv4 networks, it relies more heavily on proper firewalling.

- Due to a larger available address space for organizations, IPv6 address plans focus more on structure and aggegation, which generally allows for simpler filtering rules. One would also typically have only a single IPv6 prefix for the whole organization, but maybe multiple small IPv4 prefixes.

- Filter ULA and site-scoped multicast at site/org. boundaries.

- Apply ingress and egress filtering to drop bogons (static), spoofed addresses (wrong side of border) and internal-only addresses.

- For general filtering in dual-stack networks, make sure to keep IPv4 and IPv6 filters in sync.

- ICMPv6 filtering:

- Must be done with care, as functioning IPv6 depends on many of its types (e.g. for PMTUD, NDP, MLD).

- Can typically follow a whitelist model in network firewalls/routers, where all ICMPv6 is disabled by default. The blacklist model may be appropriate for hosts.

- Should be allowed:

- Type 1: Destination unreachable (all codes).

- Type 2: Packet too big (all codes).

- Type 3: Time exceeded (all codes).

- Type 4: Parameter problem (all codes).

- Should be allowed for troubleshooting:

- Type 128: Echo request.

- Type 129: Echo reply.

- Type 139,140: Node information query/response (maybe).

- Should be allowed on link only:

- Type 130,131,132,143: MLD (all v1/2).

- Type 133–136: NDP (only RS/RA/NS/NA).

- Type 141,142: Inverse NDP (INS/INA).

- Type 148,149: SEND (maybe).

- Type 151–153: MRD (maybe).

- Should be dropped:

- Type 138: Router renumbering (not needed, ignored without IPsec).

- Type 139,140: Node information query/response (maybe).

- Type 100,101,200,201: Private experimentation.

- Type 5–99,102–126: Unallocated error codes (maybe).

- Type 127,255: Reserved for future ICMP expansions (maybe).

- Should be dropped on link only:

- Type 137: Redirect (NDP) (if untrusted clients and not ignored by all hosts).

- For more information about ICMPv6 filtering in firewalls, see RFC 4890.

- Extension header (EH) filtering:

- Firewalls should be able to properly recognize and filter by EHs.

- RFC 7112 requires that the full header chain goes in the first fragment.

- Packets with invalid/forbidden combinations of headers should be dropped.

- RH0 should be dropped.

- Transition mechanisms:

- Makes traffic inspection and filtering a bit more complicated.

- Consists of tunneling methods and translation methods (see separate section for more info).

- Consider filtering transition mechanisms you don’t employ in the network.

- Native IPv6 uses EtherType

0x86dd, tunnel methods use a specific IP upper-layer protocol number or TCP/UDP port.

BGP

- Route hijacking:

- By originating the prefix from the adversarial AS (simple) or by forging a fake AS-path and making traffic go through the adversarial AS (complex).

- Can happen by mistake or by malicious intent.

- The route with the shortest path (generally) wins, so the adversarial route may win “nearby” and lose “far away”.

- This can be used in DoS or MITM attacks, with the latter being harder to detect.

- The MITM attack is a bit more involved as the traffic stil needs to reach the legitimate AS in the end.

- Mitigations against fake-origin route hijacking:

- Route filtering based on agreements and/or IRR databases.

- RPKI w/ authenticated origins.

- BGPsec (not widely used).

- As an emergency mitigation, announce more specific routes to win the longest-prefix-match.

- Prefix filtering:

- MANRS (Mutually Agreed Norms for Routing Security):

- A global initiative aiming to build more a secure and resilient Internet through collaborative efforts, targeting network operators, IXPs and CDNs/cloud providers.

- Network operator actions:

- Facilitate global operational communication and coordination (keep contact information up to date).

- Facilitate validation of routing information on a global scale (correctly use route objects, RPKI and document routing policy).

- Prevent traffic with a spoofed IP address (use ingress filtering and maybe uRPF) (optional).

- Prevent propagation of incorrect routing information (define a clear routing policy, use RPKI checking, use BGP bogon filtering etc.).

- Use TCP-AO for peering authentication. IPsec is not supported.

False-ish Statements

- IPv6 is less secure than IPv4, either generally or wrt. certain parts.

- Generally not true, IPv4 and IPv6 have different features and possibilities but are still pretty similar wrt. general use. When pointing to certrain parts that seem insecure or improperly designed, people often fail to realize that the same problems are often inherent in IPv4 and that there actually exists security features or methods to complement the weaknesses.

- No NAT means no protection and no privacy.

- “No protection” is completely false, that is the job of the firewall (still present in IPv6), not NAT. “No privacy” is slightly true as IPv4 NAT does indeed scramble private addresses into one or more public addresses, whereas for IPv6, the same “internal” address is visible from service providers. Especially SLAAC with modified EUI-64 addressing was vulnerable to tracking even across different end-user networks. SLAAC with privacy extensions and stable addresses does however give pretty decent address privacy protection. Although, as with IPv4, the public address (IPv4) or prefix (IPv6) is still not in any ways “hidden”, which neither NAT nor temporary addresses can avoid. TL;DR: NAT is not a security tool.

- IPv6 is a vulnerability in my IPv4-only network.

- Typically yes, actually. Unmanaged/ignored IPv6 will often mean that hosts on the network kan freely communicate between themselves and also run certain attacks, blocking all security measures implemented for IPv4. As IPv6 is often enabled by default on hosts, it must be managed at least a little, by running full dual-stack (including security mechanisms), by only running IPv6 security mechanisms (RA guard, ND guard etc. according to current IPv4 traffic policies) or by actively blocking IPv6 on routers and switches. The latter would of course keep the network in the past, prevent access to IPv6-only resources and cause a lot more work when eventually implementing IPv6, so implementing it now is often the better approach for multiple reasons.

- IPv6 is impossible to scan.

- It’s true that brute-force/naive searches trying to scan all addresses will take too many resources (and traffic), searching based on a bit of knowledge is possible. For instance, many subnets are placed early in prefixes and most static addresses are placed low in the subnet (typically within the first 1024 addresses). Scanning e.g. the first 128 addresses for all /64 networks in a /48 (65536) or a /56 (256) is managable with a low amount of resources and a bit of time. However, for hosts using SLAAC (and not modified EUI-64), this means scanning the whole /64 to find all hosts. Alternative methods include DNS resolution (made simpler with DNSSEC) and traceroutes (for network infrastructure). Overall, if you want to prevent adversaries from scanning your network from the outside, block it at the firewall. If you want yourself to be able to scan your own network, consider scraping ND caches and MAC tables from routers and switches instead (or use built-in device tracking if the network devices support it).

- IPv6 subnets are always reachable (GUA specifically).

- Traffic can be blocked using firewalls and ACLs. If the GUA prefix should truly be isolated from the Internet, you can simply not advertise routes to it. Using public addressing does not mean it must be publicly routable or reachable.

Threats

- IP spoofing:

- A simple spoofing attack where an adversary sends a packet from a spoofed source address.

- Further used in e.g. smurf attacks.

- Doesn’t work for handshaked protocols like TCP, where the source must receive a packet and then send another packet as part of a handshake, as the return packet is not sent to the adversary but to the real source host.

- Doesn’t work for authenticated protocols.

- Doesn’t allow the adversary to receive traffic intended to the real host (would require MITM or hijack).

- To mitigate external hosts spoofing internal addresses, add ingress filtering at the perimeter firewall/border router, dropping all incoming traffic sourced from internal (spoofed) addresses. For bonus point, add egress filtering dropping outgoing traffic sourced from external (spoofed) addresses.

- To mitigate spoofing internally, apply strict unicast reverse path forwarding (uRPF) for all client and server networks, preventing them from sending traffic from source addresses not part of the connected networks. This can also be applied for firewalls and linknets, but can cause problems if asymmetric or complex traffic flows are possible.

- To mitigate spoofing from clients connected to a managed switch, enable IPv6 inspection (builds a dynamic binding database) and enable IPv6 source guard (blocks packets sourced from addresses not in the binding database).

- RA and NS/ND spoofing (MITM or DoS):

- NS and NA spoofing allows hosts to redirect traffic destined to another neighbor through cache poisoning. As both NS and NA messages update neighbor caches, both may be used.

- RA spoofing allows hosts to redirect traffic destined to outside the local network by taking over the default gateway (or other routes) through cache poisoning.

- These poisoning attacks may either be used for MITM attacks (adversary poisoning neighbors’ caches with their own MAC address, then sending traffic to the correct neighbor) or for DoS attacks (poisoning with any other MAC address, so traffic doesn’t reach the intended host).

- These spoofind attacks are also present in IPv4 through ARP poisoning and rogue DHCPv4 servers.

- RAs can additionally be used to spoof specific routes on non-uplink interfaces on hosts, such that the longest-prefix-match rule causes traffic to exit through that interface even though the default gateway is found on a different interface.

- Spoofed RAs can also contain erroneous configuration to misconfigure the client, yielding a DoS. Or to set a custom DNS server, yielding a DNS MITM, often used to hijack other services.

- Mitigations include first-hop security mechanisms like RA guard against RA spoofing, IPv6 snooping (DHCPv6 guard and ND inspection) against NS/NA spoofing and optionally IPv6 source guard against traffic spoofing. RA guard lets you statically specify router ports, while IPv6 snooping builds a dynamic binding database and validates NS/NA messages against it. IPv6 source guard prevents sending traffic from spoofed addresses, i.e. those not found in the binding database. Not all switches properly support this yet.

- For servers and stuff, this is often partially avoided by using static configuration. NS/NA spoofing or MAC address spoofing may still be possible vulnerabilities, though.

- See RFCs 3756 and 6104 for more info on ND threats.

- Redirect spoofing (MITD or DoS):

- Spoofed redirect messages, containing the real router’s source address, some destination prefix and the adversary’s target address, may be used for similar purposes as RA spoofing.

- The general mitigation is to simply not accept redirects in the hosts’ configurations.

- DNS MITM:

- Through RA spoofing, the adversary can set a custom DNS server, yielding a DNS MITM. This can be used to hijack other services.

- See the RA spoofing notes for mitigations (spoiler: RA guard).

- In addition to normal DNS, keep these name resolution services in mind too:

- DNS Service Discovery (DNS-SD)

- Multicast DNS (mDNS)

- Link-Local Multicast Name Resolution (LLMNR)

- DAD DoS:

- For this attack, the adversary keeps answering DAD messages sent by a host trying to choose an address (with NS or NA messages), making it look like all the addresses it tries are already taken.

- It may also target the default gateway for the local network, if the router has just been restarted and is using DAD.

- This is a variant of NS/NA spoofing and similar mitigations should be applied.

- Node information query leaks: TODO (RFC 4620)

- Neighbor cache exhaustion (DoS):

- A DoS attack targeting the neighbor cache of routers on a /64 linknet. When the attacker sends a packet toward an address inside the /64 that does not belong to either of the linknet nodes, the router toward the linknet would attempt to look up the neighbor owning the address before marking the address as “INCOMPLETE” in its ND cache (as well as starting certain timers and stuff). Sending packets to a large number of addresses on the linknet will eventually exhaust the ND cache of the router and potentially steal a large portion of control plane processing power. For addresses hitting solicited-node multicast groups used by neighbors, the neighbors will potentially spend a large amount of control plane processing power on simply discarding the packets.

- Rate limiting ICMP can help reduce the attack, but can in certain cases escalate the DoS if either router fails to form neighborships due to dropped ICMP messages.

- A simple mitigation is to use /127 networks for P2P links, or slightly larger if more than two nodes use the linknet. However, this is more of an old hack and is no longer recommended.

- Another mitigation is a new feature implemented by multiple vendors, called “IPv6 Destination Guard” (Cisco). Instead of sending neighbor solicitationt on linknets, it uses ND gleaning and ND refresh timers to find neighbors.

- Rogue DHCPv6 servers:

- Just like rogue DHCPv4 servers, but requires the RA to have the M and/or O flag set to tell the host to use DHCP.

- May be used to assign adversarial DNS servers (MITM), bad IPv6 addresses (DoS) or other options. The default gateway address can’t be set, that’s configured by RAs in IPv6.

- This may be used in combination with a DHCP exhaustion attack to prevent the legitimate server from being able to assign any addresses.

- Like DHCPv4, enable DHCPv6 snooping, which prevents untrusted ports from sending server messages.

- DHCP starvation (DoS):

- A client requests a ton of IP addresses using different DUIDs and exhausts the address pool.

- First-hop security may be used to mitigate this.

- MLD report flooding (DoS):

- Sending loads of MLD report messages might exhaust the router’s resources.

- To limit memory usage, set a limit for the number of MLD entries on the router.

- To limit control plane processing, rate limit MLD messages.

- As a more drastic solution, disable MLD if not needed.

- MLD amplification attack (DoS):

- Sending generic query message with the router’s address as the spoofed source, a lot of reports will be sent to the router.

- Like MLD flooding, you should rate limit MLD messages on the router, or potentially disable MLD if not needed.

- MLD protection on switches in the form of an ACL that blocks incoming MLD queries on downlinks will prevent this.

- MLD scanning:

- Passive scanning: Snoop on MLD messages on the link. Since all host must join at least one group, all conformant hosts can be eventually be found.

- Active scanning: Send queries and listen for reports. Using MLD protection will prevent this.

- As certain OSes always join certain groups, you can get a rough fingerprint of the OS of a host.

- Traffic class and flow label as covert channels:

- The two fields in the IPv6 header may be used to smuggle information between hosts, unnoticed by simple security tools.

- Can be mitigated using a proper IDS/IPS that checks the header fields.

- The traffic class is only expected to exist within trusted traffic policy domains and should be wiped or ignored when sourced from untrusted networks/clients.

- The flow label is currently not used by the majority of networks, although it could be a bad idea to simply wipe it as might interfere with future use.

- Routing header type 0 (RH0):

- Packtes using the routing extended header with routing type 0, allowing the sender to specify up to 127 addresses to visit in the path. This enables a DoS where the adversary targets two ends of a link/path and makes the packets ping-ping back and forth between those two routers around 126 times (roughly a 63x traffic amplification).

- Mitigated by not allowing RH0 routing, either by using RFC 5095-compliant routers (which deprecated RH0) or by blocking packets with the RH0 header in firewalls.

- Bypassing RA guard or similar by using extension headers:

- The idea is that you can trick security devices or RA guard features if using extension headers. Very simple implementations may e.g. only look at the “next header” value of the base header and miss that it is an ICMPv6 packet if there exist any extension headers.

- Proper implementations should handle this properly.

- Bypassing RA guard or similar by using fragmentation:

- This is similar to the last bypass threat, but based on the fact that the original packet must be reassembled in order to check for RA messages or similar. As RA guard is implemented at switch level, reassembly is generally not an option.

- The mitigation is simply to forbid using fragmented NDP packets, as is now standardized. This means that security devices and switches can ignore fragmented RA messages since compliant hosts are forced to discard them anyways.

- RFC 7112 describes a related mitigation, where the full header chain should (must?) always go in the first fragment, so only the first fragment need to be inspected to check for e.g. ICMP messages. It also describes some RA guard-specific stuff.

- General fragmentation threats:

- Partial header chain in first fragment:

- RFC 7112 requires that the full header chain must go in the first fragment. This makes traffic inspection much easier.

- This can be caused by creating lots of tiny fragments, such that upper-layer headers no longer go in the first fragment.

- Firewalls should filter non-conformant packets.

- Fragments inside fragments:

- Multiple layers of fragmentation, making traffic inspection difficult.

- This should not happen as only one fragment header is allowed. The firewall should silently discard such packets.

- Fragmentation inside tunnels:

- A proper NGFW or IDS is required to inspect this traffic.

- Overlapping fragments:

- Can cause problems in vulnerable operating systems, yielding e.g. the Teardrop DoS attack or IDS bypass attacks.

- RFC 5722 requires that datagrams containing overlapping fragments must be silently discarded.

- Not sending the last fragment:

- Can cause resource exhaustion in hosts, which keep waiting for the last fragment before completing the reassembly.

- RFC 8200 establishes a fragment reassembly timer, starting with the first-arrived fragment. If the time runs out, all fragments must be silently discarded. It defaults to 60 seconds.

- Atomic fragments:

- Fragments with fragment offset 0 and M flag 0, meaning it’s a only single fragment.

- Such fragments may be crafted by an adversary to cause overlapping fragments for an existing stream of fragments, forcing the host to discard the original datagram.

- RFC 6946 requires hosts to process atomic fragments in isolation from normal datagrams and non-atomic streams of fragments.

- Partial header chain in first fragment:

- ICMPv6 error messages for packets sent to multicast addresses:

- This could be used for discovery and amplification attacks if all nodes listening to the multicast address were to respond with ICMPv6 error messages, e.g. in Smurf attacks.

- ICMPv6 partially solves this by forbidding sending error messages in response to packets sent to multicast addresses, however, this does not apply to “packet too big” and “parameter problem” (RFC 4443).

- The above exception means that “paramteter problem” may still be used for network discovery, by crafting an invalid packet and sending it to the all-nodes link-local multicast address.

- As a side note, responding to a multicast ping (“echo request” sent to a multicast address) is optional and most OSes don’t do this by default. This could be used in Smurt attacks (traditionally with IPv4 local or directed broadcasts and a spoofed source address).

- DDoS attacks:

- Works just as for IPv4.

- An additional threat for IPv6 is the RH0 amplification attack, which should hopefully not be relevant any more with updated implementation and filtering where required.

- With the address expansion from e.g. IoT and lack of NAT, IPv6 DDoS attacks are likely to participate with more unique addresses than for IPv4.

- As IPv6 is often a bit more neglected than IPv4 from both network designs and software/firmware implementations, there’s likely less active security measures for IPv6 than for its IPv4 counterpart.

- As IoT devices are both growing in number and often have somewhat neglected security mechanisms, they’re a prime target for infecting and including them in the attack.

- Protection:

- Use location-distributed services with anycast addresses, to force target distribution of the attack.

- Use cloud-based or ISP-based scrubbing services in front of your own services. Make sure they can’t be easily bypassed.

- Use remote-triggered blackholing (RTBH) through the well-known BGP community, to stop the traffic before reaching your network, if your ISP supports it.

- Use IPSes to automatically prevent the attack from reaching further into your network.

- Use automation to detect DDoS attacks and dynamically apply filtering on routers or firewalls (e.g. a special ingress filter for ongoing attacks).

- To avoid having your devices infected and participating in attacks against other parties, apply appropriare security measures to protect them.

- Transition mechanism attacks:

- Disable unused transition mechanisms on hosts, e.g. ISATAP, to prevent automatic tunnels.

- Filter unused transition mechanisms on firewalls.

- Filter “translated” traffic from interfaces/zones it’s not supposed to come from.

- NAT64/DNS64-based attacks:

- IP pool depletion attack: Standard dynamic NAT/PAT exhaustion.

- Processing overload attack: Flooding traffic with protocols that contain L3 information and requires special treatment, like FTP.

First-Hop Security Mechanisms

- IPv6 RA Guard:

- Prevents rogue routers trying to advertise (primarily) the default route and steal traffic from other hosts on the subnet, similar to DHCP snooping plus IPSG for IPv4.

- Can be mitigated either using custom port ACLs (blocking RAs from downlink ports) or using the RA Guard feature present on most managed switches.

- IPv6 Destination Guard:

- For use on linknets, to mitigate the neighbor cache exhaustion attack.

- This should always be used if using /64 linknets. However, if using /127 or similar, this is not needed (same as for IPv4) (see RFC6164).

- It prevents the router from sending NS-es and instead uses ND gleaning and ND refresh timers to form neighborships.

- TODO: Move Cisco example to Cisco pages.

- Config statements (Cisco IOS):

- Define policy (global):

ipv6 destination-guard policy main(using namemain) - Set enforcement (policy):

enforcement always(orstressed?) - Apply policy (interface):

ipv6 destination-guard attach-policy main

- Define policy (global):

- Operational commands (Cisco IOS):

- Show status:

show ipv6 destination-guard policy <name>

- Show status:

- TODO

Address Planning and Implementation

Random Notes

- It should support both IPv4 and IPv6, potentially IPv6-only if appropriate.

- IPv6 should be native.

- IPv4 may be provided through dual stack or as a service using translation or tunneling mechanisms.

- IPv4 may can be tunneled both over internal core networks and through the internet edge.

- If tunneling is appropriate, use 6rd, tunnel brokering or proto 41 forwarding, not ISATAP, 6to4 or Teredo. Prefer stateless.

- Try to avoid NAT.

- For ISPs, native IPv6 with CGN for IPv4 is appropriate since IPv6 is proprotised and will offload IPv4.

- Internal addresses:

- Should be IPv6-only.

- May use either GUAs or ULAs.

- Interfaces with ULAs which need internet access may:

- Be assigned a GUA in addition to the ULA.

- Use NPTv6 to translate the ULA prefix to a GUA prefix (avoid if possible, use GUA instead).

- NAT66 is not required for ULAs and should not be used.

- ULAs provide global address independence.

- ULAs without NPTv6 provide an extra layer of protection for systems that should not be accessible externally.

- Sites should get a prefix long enough for multiple subnets.

- Typically around 48.

- Find out how much space you need before requesting it.

- If you didn’t get enough, ask for more.

- All subnets should be /64.

- Convention where all networks are of the same length, making “/64” synonymous with “network” and makes all networks addressable with exactly 64 bits or 16 hexadecimals (ignoring zero compression).

- Address conservation should not be taken into account, there’s enough /64 prefixes.

- Avoids pointless VLSM, a thing of the past.

- Required by e.g. SLAAC and unicast-prefix-based IPv6 multicast addresses (RFC 3306).

- Even point-to-point links should get their own /64 reservation.

- Topology aggregation VS policy/service aggregation.

- For LIRs, separate LIR infrastructure space from end user space (a few non-contiguous IP addresses should however be in LIR space).

- Suggested information to include in the prefix:

- Region.

- Location.

- Service type.

- Application.

- Subnet.

- VLAN ID (12 bits) (if the address plan is closely tied to the VLAN plan).

- Assign a /48 to each POP.

- Use provisioning tools (IPAM).

- Don’t mirror the IPv4 address plan with all of its legacy problems.

- Plan both for now and for the future.

- Subnet on nibble boundaries.

- Makes the address plan clearer since one nibble is one hexadecimal digit, so you avoid ranges within a digit and so you probably won’t need a subnet calculator with a little bit of practice.

- Can roughly be compared with subnetting on bit boundaries for IPv4, since the address space is four times larger.

- Makes the address plan much more uniform while only sacrificing a small bit of granularity.

- Allows for DNS reverse zones that match exactly the prefixes.

- Leave space for future expansion within prefixes. Avoid having to create multiple prefixes for the same purpose due to lack of space.

- GUA VS ULA.

- SLAAC VS DHCP.

- Android and Chrome OS does not support SLAAC, by design.

- DHCP provides more accountability.

- Implement appropriate first-hop security mechanisms, such as ICMP guard and DHCPv6 guard.

- Consider blocking certain multicast addresses, especially with site scope, to prevent attackers from identifying certain important resources on the network.

- Deploy both perimeter and host-based firewalls.

- Consider identity-based firewalls.

- Implement IPv6 in existing IPv4-only networks step by step. Either in phase with equipment lifecycles or as part of a needed redesign.

- Make sure Teredo is disabled on all clients not explicitly needing it.

- GUAs should use the privacy option to prevent tracking. This includes ULAs using NPTv6.

- PI space (provider independent) can be aquired to prevent network renumbering.

- Consider multihoming:

- Redundancy and load balancing.

- Potentally lower costs if the ISPs offer different prices for different services.

- IPv6 supports native multihoming since interfaces can be assigned multiple prefixes from different routers.

- RFC 7421 provides an analysis of the 64-bit boundary in IPv6 addressing.

RIPE: IPv6 Fundamentals course

- A subnet in IPv6 is a /64.

- The recommended prefix length for a loopback interface is a /128.

- It is recommended to reserve a /64 for each P2P link, even if you end up configuring a /127 on the router interface.

- It is common to see POPs with a /48 address space as a minimum. It is common practice to assign to an End User a prefix size between /48 and /56.

Philip Smith: IPv6 Address Planning (2012)

IPv6 BCP according to APNIC.

- Focus on scalability and ease of use/application of security policies and network management.

- IPv6 allows creating a more flexible address plan.

- Always segment on nibble boundaries. Makes it simpler.

- Allocate:

- One /48 for the infrastructure and other “units”. Allocate separate ones for customer links at each PoP.

- Use the first /48 for infrastructure, to keep important addresses short.

- Within each /48, allocate all loopbacks within the first /64.

- Allocate linknets as separate /64s but address as /127.

- Allocate /64s for each LAN.

- Customers generally get a /48.

- Design a scheme to keep some structure.